Scent has comfortably been making a home in art galleries around the world. The 2021 “Fleeting – Scents in Colour” exhibition allowed its visitors to smell the artworks they were seeing through commissioned fragrances created by IFF; the 2012 “The Art of Scent” exhibition at the Museum of Arts and Design was an early entrant to the category.

“Research has shown that you remember something better if you are smelling at the same time as seeing, so it's a good idea to combine the two. They perceive the museum in a different way. Your memory of the experience is stronger. People have a curiosity and want to have novelty,” Gregorio Sola, Senior Perfumer at Puig and the nose behind the scents at “The Essence of a Painting. An Olfactory Exhibition,” told BeautyMatter in 2022.

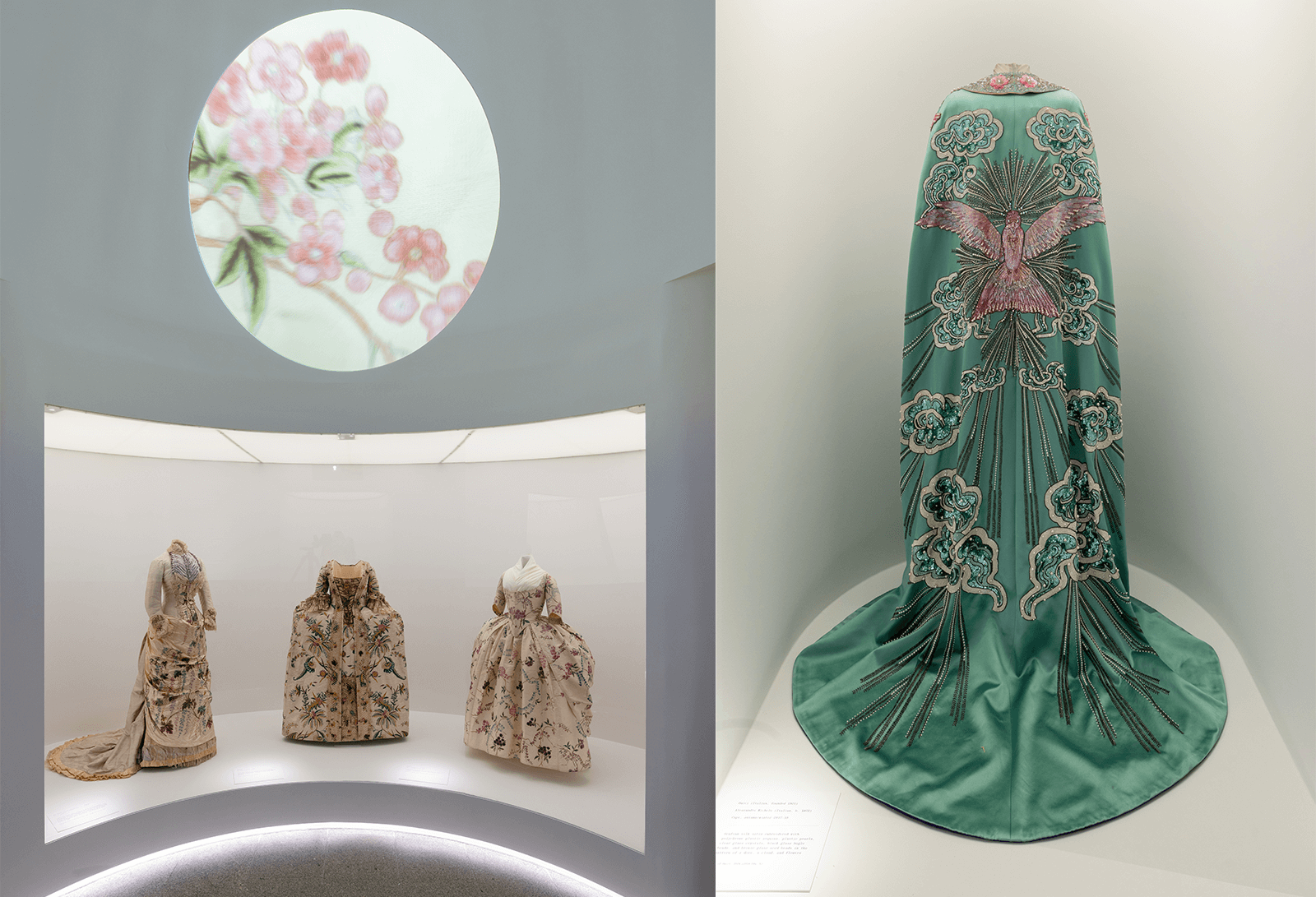

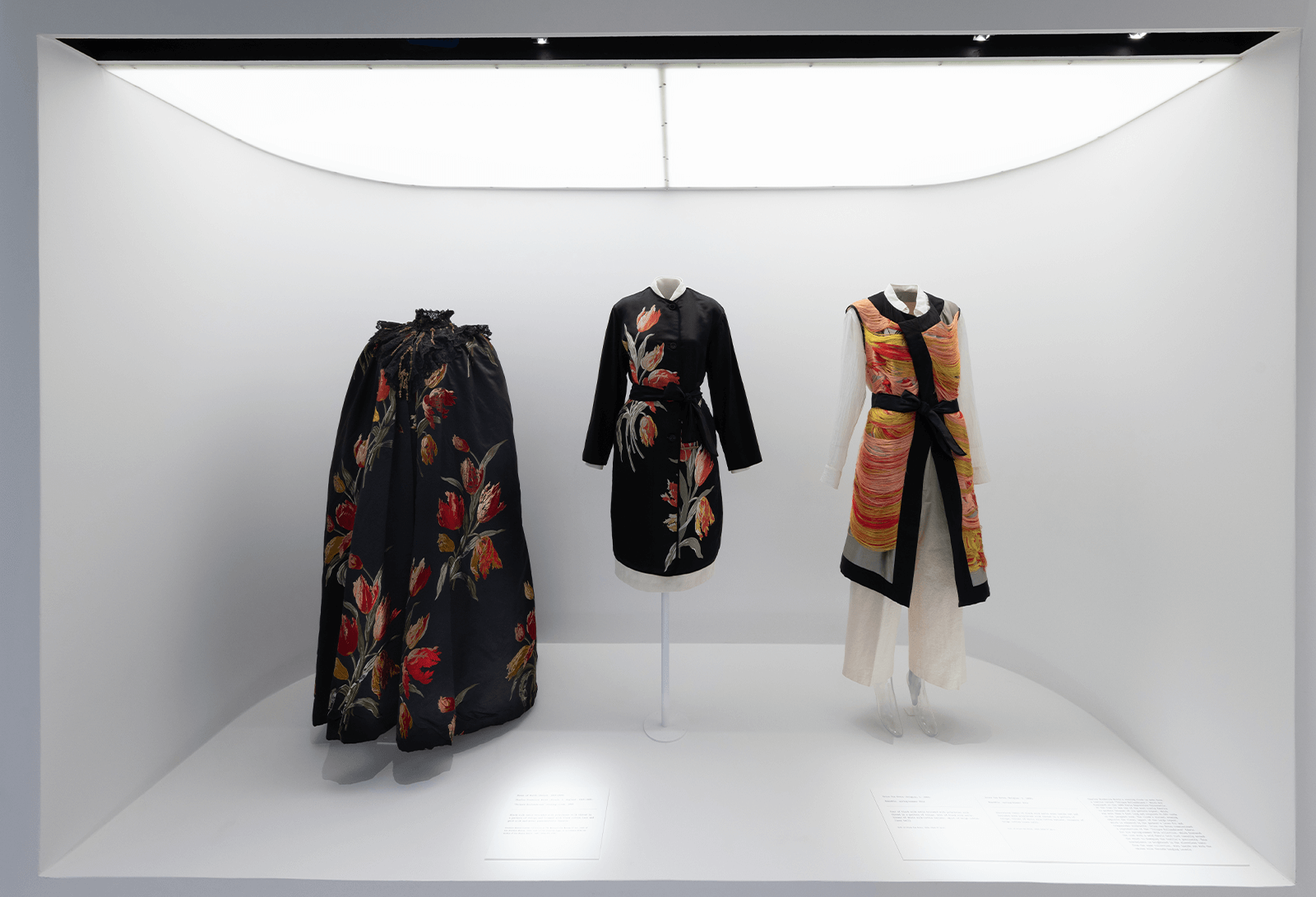

Now, in perhaps one of the most publicized annual show openings, the Metropolitan Museum of Art has incorporated the medium into its “Sleeping Beauties: Reawakening Fashion” exhibition. Its name is derived from the garments so fragile in nature that they have to be laid down in displays, which are dispersed throughout the show. Designers on display include Loewe, Charles Worth, Mary Katrantzou, Dior, Rodarte, Alexander McQueen, and Maison Martin Margiela.

Running from May 10 to September 2, the show features 250 objects from the museum’s collection, with nature—organized into three separate sections of earth, air, and water—acting as the red thread connecting them all. Other sensory elements apart from sight are also included, with the embroidery of select garments embossing the walls of the space for viewers to touch. Digital artwork and various technological activations (including 3D-printed garment replicas), created courtesy of SHOWstudio and the creative consultant Nick Knight, provided further immersive visual elements.

“When an item of clothing enters our collection, its status is changed irrevocably. What was once a vital part of a person’s lived experience is now a motionless ‘artwork’ that can no longer be worn or heard, touched, or smelled. The exhibition endeavors to animate these artworks by reawakening their sensory capacities through a range of technologies, affording visitors sensorial ‘access’ to rare historical garments and rarefied contemporary fashions. By appealing to the widest possible range of human senses, the show aims to reconnect with the works on display as they were originally intended—with vibrancy, with dynamism, and ultimately with life,” Andrew Bolton, curator of The Costume Institute, states.

The synaesthesia-esque approach of the show challenges the viewer to consider all the way in which a garment can be experienced, especially in delicate pieces where touch is not a possibility. Max Hollein, the Museum’s Marina Kellen French Director and Chief Executive Officer, adds: “The Met's innovative spring 2024 Costume Institute exhibition will push the boundaries of our imagination and invite us to experience the multisensory facets of a garment—those facets that deteriorate and become lost after entering a museum collection as an object. “Sleeping Beauties” will heighten our engagement with these masterpieces of fashion by evoking what it was like to feel, move, hear, smell, and interact with them when they could be worn, ultimately offering a deeper appreciation of the integrity, beauty, and artistic brilliance of the works on display.”

As for the sensory aspect of smell, while the male ensembles created by Francesco Risso for the Spring/Summer 2024 Marni collection were sprayed with a creation by perfumer Daniela Andrier, inspired by Risso’s encounter with a young man on a visit to Paris, scent artist and researcher and self-proclaimed “professional in-betweener” specializing in chemical communication Sissel Tolaas dove even deeper. “The long-term research I am doing for the Met—and specifically the Costume Institute Archives for the “Sleeping Beauties” exhibition—is to seriously track hidden information in archival materials, information one does not see but information that can be core for understanding the items properly, Tolaas tells BeautyMatter. “I use forensic chemistry for this purpose. I have been working in the labs for over a year, and with the help of advances in technology collecting the smell molecules emitting from up to 100 items (case studies for the exhibition and beyond).”

Tolaas, with support from Symrise, reproduced the smell molecules in the garments by first extracting them with a microfilter in a glass barrel with a battery-powered pump for 1-2 hours. Said microfilters trap air and moisture while extracting the smell, this data is then analyzed through gas chromatography–mass spectrometry to identify and replicate them.

The 10 overlapping molecules found in a 1958 Dior “Rose Rouge” evening dress and a 1923 “Roseraie” Lanvin evening dress were displayed in test tubes. The components found were: benzaldehyde (present in honey and almonds); caprylic acid (found in rancid and oily animal products); benzothiazole (present in sulfurous food); coumarin (found in tobacco and hay); methyl salicylate (present in pharmaceutical products for muscle aches, as well as in acidic fruits when in touch with human skin); diethylphthalate (present in rubber and bitter drinks); phenoxyethanol (present in polluted environments and faint rose smells); isodragol (present in high-end skincare products, plants, and fruits), octane (present in motor oil and gasoline); undecane (a sex attractant for cockroaches and moths); and tetracosane (present in dental products).

Another example included a 1913 “Rose d’Iribe” day dress worn by Denise Poiret (wife of Paul Poiret) and a 1913 House of Drecoll silk dress. The smells found in both was applied as scented paint on the walls opposite of the display. Fashionable heiress Millicent Rogers was the subject of the “Scent of a Woman” section, with her worn garments including a 1938 Schiaparelli evening dress, 1943 Mainbocher cocktail apron, and 1942 cocktail hat. The six peak molecules found were: hexadecyl 2-ethylhexanoate (present in emollients,coconut oil, and cosmetics; palmitic acid (from plants, animals, microorganisms, and oils); butyl cellosolve (created when body sweat mixes with surfactants; menthadien-1-ol (present in decaying natural materials); beta-phellandrene (present in products containing pepper); and dodecane (present in plants, including ginger).

“All the molecules [in the exhibition] are real molecules found in the various items. What you are smelling is not fake but actual amplification of hidden information under the ’skin’ of the items,” Tolaas adds. “What all these smells do is bring back or reawaken hidden life in all the items of concern. Visitors can engage with the items and exhibition through emotions and memory in the most efficient way and start to imagine the people who have been wearing the various garments.”

For Tolaas, the message of her smell projects for the show go beyond the walls of the Met museum. “We live in a world where we look at things and frame view. Smell embodiments bring immediate emotion to that understanding. Without an emotional reaction there is no action,” she concludes. “People love to smell real stuff. For the first time in history the Met is opening a new way of communication for their massive archive, and that is sending an incredible sign of change to the world. I am very thankful for being part of this change.”